In the last few years, the US Bureau of Labor Statistics reported that about a third of the workforce is regularly exposed to the outdoors for their jobs; on the other hand, most robotics research occurs in controlled indoor environments (for good reason). I suspect that this gap, if left not prioritized, could lead to a disappointing path for automation, moving more humans outside to perform manual labor as large language models (LLMs) reduce need for the more comfy office jobs. Over the last year, I’ve been delving into robotics, focused on using cobot (collaborative robot) arms—which are lightweight and designed to operate safely around humans—to execute pick-and-place tasks and, more generally, dexterously manipulate objects in outdoor, largely unstructured environments. Bringing a robot outside, however, introduces a plentitude of problems ranging across hardware to software, so I started my journey with an indoor test environment using plastic and metal to recreate objects and environments I would face outside. After first exploring a classical approach, which I define below, I moved into more modern and flashy end-to-end methods, namely ACT, Diffusion Policy, and VQ-BeT; I compared these models and note in this post some observations and takeaways for anyone else applying or curious about offline imitation learning for visuomotor control in dexterous tasks.

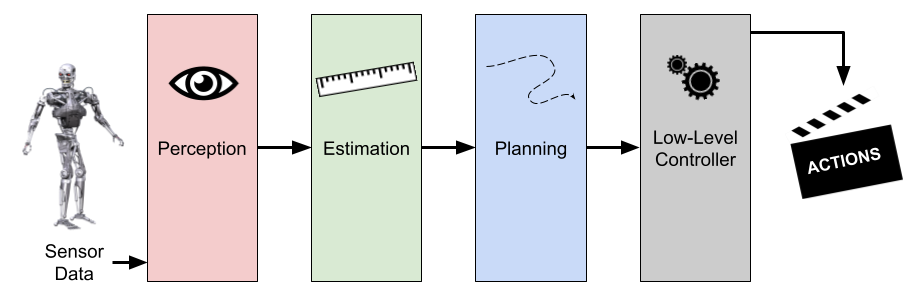

Before launching into the policy analysis, it’s worth explaining why I did not continue with an easier-to-explain modular framework for robot control. I first implemented a classical control pipeline, which can be very broad and fuzzy in definition, but I will define as a framework with explicit modules for perception, estimation, and high-level planning that commands a lower level controller to move the robot.

- the depth map not being dense enough for objects far from the camera

- poor mesh fitting due to occlusions or noisy depth

- the classical planner failing to find a safe path to the grasp pose

- danger from smacking into things that had not yet been mapped as collision objects.

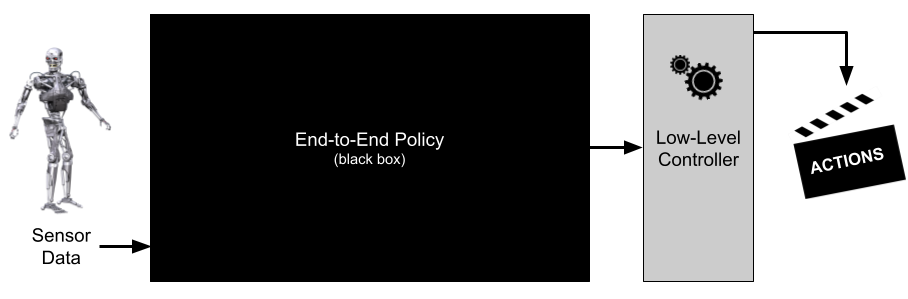

End-to-end frameworks approach the problem differently by ingesting sensor data and directly predicting actions, handling everything from one end of the task to the other end. Some view this as incredible and a huge convenience in approaching difficult challenges in robotics (it’s all taken care of for you! 😀). Still, others take a more skeptical stance and point out the lack of guarantees a black box approach can offer (it’s all taken care of for you…🤨).

…the space of possible object states, contact dynamics, and task variations is combinatorially large, making it impossible to encode effective strategies through explicit rules or heuristics. Consequently, current state-of-the-art approaches are predominantly data driven, leveraging deep learning to automatically learn robust representations and control strategies from demonstrations or large-scale datasets. Yet, even these approaches face significant challenges, since robots must operate in dynamic and unstructured environments, where not only object properties and task goals but also environmental conditions—such as lighting, clutter, occlusions, or background changes—can vary unpredictably. To address these difficulties, imitation learning has emerged as a powerful paradigm, enabling robots to acquire complex skills directly from human demonstrations.

In the past few years, there has been a surge in offline imitation learning (learning to predict actions from observations via supervision on collected trajectories) research and applications, proving to be a very effective alternative to classical control or learning from reward with reinforcement learning. Curious about the results, I investigated two fan-favorite policies in the field: the Action Chunking Transformer (ACT) and Diffusion Policy (DP). I also trained VQ-BeT from Lerrel Pinto’s lab for good measure. I chose not to go down the VLA (policies that also consider language prompts when predicting actions) route for the time being since I wanted to focus on a single pick-and-place task, and intuition tells me that natural language will offer little edge on a task where the challenge lies predominantly in tricky spatial reasoning over semantic understanding (i.e. there was no blue box vs red ball for me to distinguish between with a prompt “grab the red ball”)1.

With the classical method, I had started in an indoor environment with a rough analog to the outdoor task to enable rapid testing. After devising a means for teleoperation (a system for puppeteering a robot to collect data that ties sensor observations to manipulator actions), I set out to learn the indoor task proxy as a proof of concept. This decision showed to be double-edged as I am pretty confident that familiarizing myself with the vision-based teleoperation and imitation learning paradigm in a chaotic and unstructured outdoor setting would have slowed my developing proficiency, however as I’ll cover in another article, the leap from the indoor setting to the outdoor setting turned many findings on their heads.

In the glorious air-conditioned, fluorescent-lit, static and consistent indoor environment, I gradually built an understanding around which models and hyperparameters were effective for the task at hand. One lesson I learned quickly was the data efficiency of ACT. To address the problem of action multimodality (e.g. one teleoperator twists a door knob clockwise, the other teleoperator twists a door knob counterclockwise—what should the robot do?), a generative component of some form is typically part of the policy’s model architecture. For ACT, they use a CVAE (very similar to the VAE but with an added conditioning variable before decoding, see me for more) during training to compress the joint observation and action sequence down to a “style” variable, where the prior is a zero-centered Gaussian. So during training, the policy samples from the posterior over this style variable, while at inference it replaces the latent with the prior mean (i.e. zero) to capture the average style.2 Passing the images through a lightweight pretrained ResNet, these two representations of the action’s style and images are input to the main course: an encoder-decoder transformer that spits out the next predicted action. This architecture leads to a zippy training with quicker results on a dataset. Of the three model families, ACT repeatedly showed the most promising results the quickest.

The first indoor dataset learned had a lot of variation in target object placement and added distracting objects. This was quickly determined too ambitious after all the models failed to even successfully approach the target, so I collected a much simpler dataset where the distractors were removed and the target object was returned to the same location and pose after each pick-and-place demonstration. The dataset contained 26 teleoperated demonstrations in total, and all models trained used joint space for action representation.3 After ACT reached a validation loss of around 0.01 radians—indicating an average motor error less than 1º—it performed the task beautifully. However, shifting the target object’s location around, revealed the model had drastically overfit to its proprioception (fancy way of saying “joint states”, or the motor values), ignoring imagery all together. On the same simple dataset, Diffusion Policy failed to approach, choosing instead to shake violently and move erratically. In hindsight, 26 demonstrations was not nearly enough data to train diffusion, a relatively more data-hungry process that learns to predict and remove noise to yield actions rather than directly predict the actions like ACT or VQ-BeT. After training VQ-BeT and being careful to watch its VQ-VAE loss before launching the main GPT training phase, I saw the model successfully complete the task (although quite shaky) which was encouraging.

Looking at the GradCAM visualization of the pretrained and finetuned ResNet18 proved a useful tool for understanding failure modes. In cases where ACT was overfitting to actions and moving to some average location in the dataset rather than towards the target, the features would often be attending to parts of the end effector visible to the eye-in-hand camera and not the target. My intuition for this behavior is that, if the model is learning that the current joint states are a better indicator of what the next action will be rather than the target object in its view, it would naturally pay closer attention to the parts of its joint states visible to the camera.

The other way to tell that ACT was overfitting to information from its joint states was observing its behavior when I covered up the camera. If there was little to no reaction to full obstruction of its visual features, then I would know something was fishy. Later models I trained would develop a recoil-like response when I blocked the camera, indicating some reliance on camera input to determine whether it’s moved too close to something. One solution to the problem of action overfitting can be further increasing dataset diversity. By moving the target object around in enough trajectories, a policy will hopefully come to rely more heavily on image observations as memorizing actions becomes insufficient. With DP utterly failing, VQ-BeT showing signs of life, and ACT clearly overfitting, I collected more indoor datasets with added variability in target location. This decision did the trick for ACT; I could clearly see the arm approaching target objects placed in different locations rather than an average “sweet spot”. Visualizing the ResNet18’s 2D activations supported this idea since the target object was now lighting up in the heatmap (see above GIF for activations focused on the cup). Although the success rate was still somewhat low, it was exciting to see the policy had also learned emergent properties like recovering from a failed grasp.

Finally, upon merging most of my indoor datasets into one monster dataset and upgrading the vision encoder to a finetuned ResNet34, DP’s performance improved significantly. This highlights the importance of larger, more diverse datasets when training a diffusion model as well as its sensitivity to the conditioning signal since small scene perturbations yielded noticeable effects on the predicted trajectory. A stronger vision backbone provides richer conditioning to the U-Net, which in-turn gives more stable action predictions. Unlike ACT, which uses the vision encoder features in a single forward pass (although the features can be used multiple times via attention), DP uses iterative denoising where the features are injected at each iteration, so noisy backbone signals can easily lead to compounding error. The challenge may also stem from gradient flow—ACT’s weights receive straight supervision from the L1 loss between predicted and actual actions, while DP’s gradients are indirect since they do not directly reflect this action error, coming instead from the denoising objective. As a result, more training time and training data allows the weights to marinate in the data longer and make sense of a weaker gradient signal.

These were some of my findings from exploring application of current SotA offline imitation learning policies to indoor dexterous tasks in preparation for taking things to the next level: THE GREAT OUTDOORS (stayed tuned).

Update: As I read more about VLAs, I’ve grown more impressed with the intra-task generalizability they can offer by pairing a text prompt with the images. By telling the policy to focus on a target object via language, it would make sense that the encoder attends to more relevant information from an image of a visually novel environment than an encoder without the prompt (e.g. trying to find a fish in a camouflaged scene). However, after adding an LLM to digest the prompt and fusing image+language streams with multimodal layers, the overall VLM tends to be one or two orders of magnitude larger than just using the vision backbone. This can make a big difference on compute requirements at inference time. ↩︎

In practice, the CVAE is sometimes disabled for boosted performance, meaning ACT simplifies to a transformer mapping observation to action with no generative component, i.e. traditional Behavior Cloning. The author of the VQ-BeT paper, Mahi Shafiullah, commented that CVAEs theoretically capture multi-modality but practically tend to collapse into a unimodal distribution. Their shift to discretized actions with a VQ-VAE as their generative component allowed them to better model robot data collected by many different people. ↩︎

In hindsight, this wasn’t really all that fair for Diffusion Policy as the original paper only shows learning task space (i.e. end effector pose), making no mention of joint space representation. A note for practitioners: Feed task space to DP! I’ll talk more in-depth about this in a later article. ↩︎